Come together. Visioni della REM Up To You 2023 su The Privileged di e con Jamal Harewood

Io prima di entrare lì già avevo paura, e poi quando ho visto le buste numerate sopra le sedie mi sono assicurata di scegliere un posto non numerato. Io guardavo intorno a me, guardavo le persone, guardavo i pezzi di pollo fritto sparsi a terra in quel corridoio bianco. C’era quell’orso steso a terra immobile. Qualcuno ha deciso che dovevamo aprire le buste, iniziando dalla numero uno. Ho accettato. Penso che tutti fossero d’accordo, o quasi. Lì è iniziato il nostro percorso di protagonismo di fronte ai fatti, lì è iniziata la nostra tragedia.

Daiane Torres

Jamal Harewood, a performance artist that makes theatre from the perspective of a black man. È lui stesso a presentarsi così in questo video sulle cinque lezioni che ha imparato dalla sua performance The Privileged, “from my Polar Bear Teacher, Cuddles”. Cuddles – Coccolino – è l’orso polare incarnato dal performer inglese con un costume da peluche gigante e che il pubblico trova addormentato al centro della scena costruita da un rettangolo di sedie sul quale sedersi. Ben presto si scopre che l’unica possibilità di azione drammaturgica – svegliare l’orso – è imposta proprio al pubblico, che aprendo le buste disposte su alcune sedie è chiamato a confrontarsi con la provocazione del perfomer che spinge all’estremo il patto di finzione tra artista e spettatore, fino ad annientarlo. The Privileged è una interactive live art performace led by the audience: è il pubblico che decide se accettare il privilegio, se combatterlo o se sottrarsi. Con un dispositivo costruito apposta per guidarti nell’incontro con l’orso polare, Harewood indaga gli effetti di razzializzazione, razzismo e identità nella comunità. Il risultato è un’esperimento collettivo che scava nel singolo e allo stesso tempo mette in dubbio le regole del gruppo. Ogni replica è diversa dall’altra, perché ogni nuovo pubblico costituisce una nuova comunità, con le sue regole da costruire. Esperimento, processo, costruzione di uno spazio e di un ambiente nel quale chiedersi: fin dove posso, fin dove possiamo? La provocazione di Harewood è talmente potente e ben incarnata che nell’invito alla finzione ci ritroviamo ancora più reali e nudi. Un’esperienza talmente intensa che ha poi bisogno di un momento di rielaborazione collettiva; l’artista lascia uno spazio al pubblico, un luogo altro da quello della performance, senza nessun conduttore, dove poter condividere riflessioni, sfogarsi, giustificarsi o anche solo ascoltare le altre persone.

The Privileged termina così, senza fine e senza applausi, abbandonandoti a fare i conti con te stesso. The Priviliged wouldn’t exist without you.

Di seguito, l’intervista che la REdazione Multi.lingue/Come Together del Festival ha fatto a Jamal Harewood dopo aver preso parte alla performance.

Luca Lòtano e Valeria Tacchi

L’intervista a Jamal Harewood

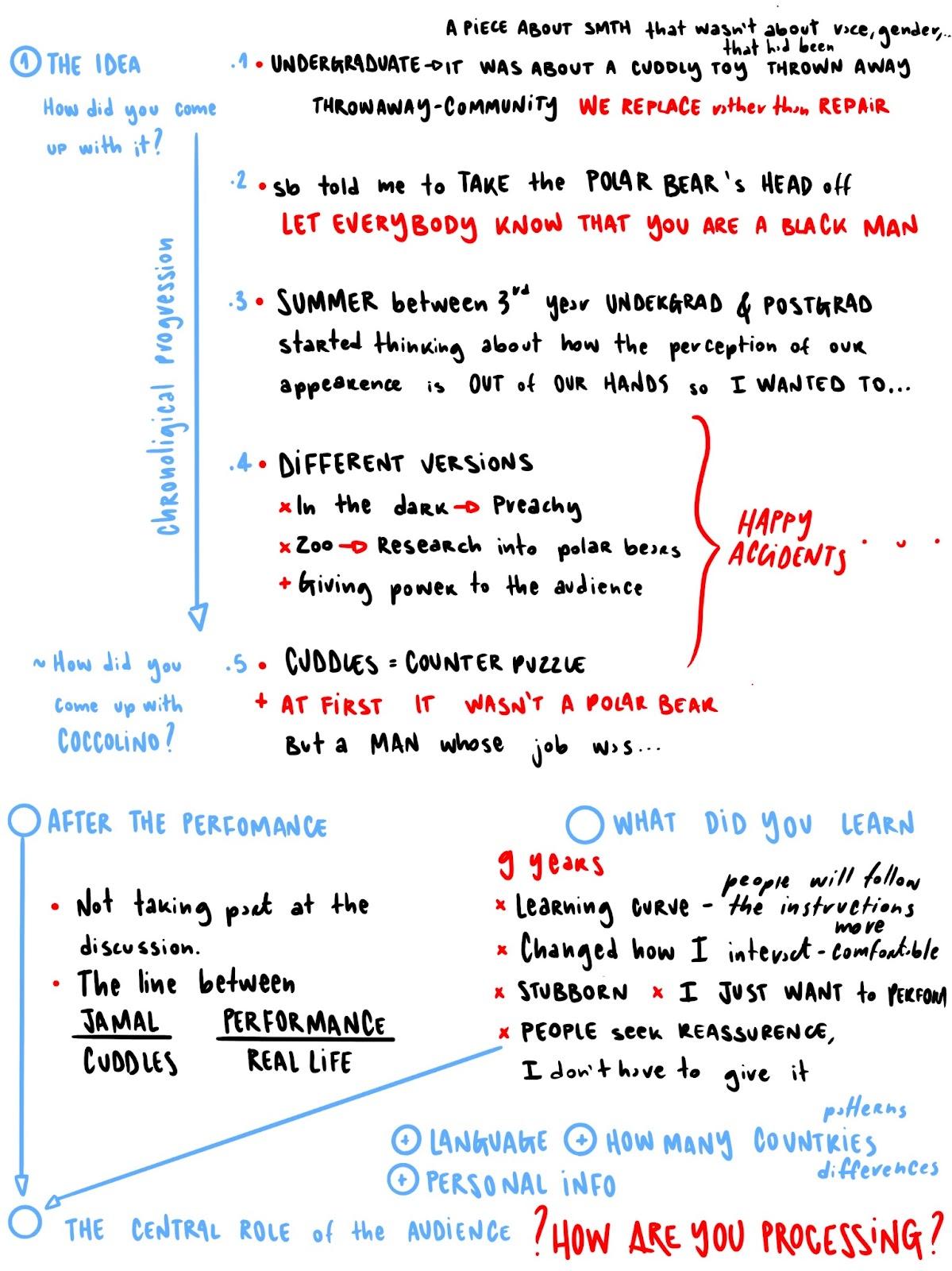

How did you come up with the idea of The Privileged?

During the summer of my third year to go postgraduate, I started thinking about how the perception of our appearance is out of our hands. So, with that in mind, I didn’t like the idea of the things I wanted to talk about being hijacked by other people and their thoughts. So, in terms of The Privileged, I was adopting stereotypes that people would put on me, and I’m making everybody experience those.

In terms of how I made it, at first, I did a lot of research into stereotypes. Then at some point I went to the zoo. I don’t even know if I saw polar bears… Well, I already had the outfit because of one piece about being in a throw-away community I made during my undergrad. So I just latched onto the zoo and latched onto the polar bear. And then, researching polar bears, I found out that they have translucent fur, which is white-ish. Underneath that, they have black skin. So it worked because I’m a Black man, and the outfit is white. It jst worked. I don’t want to say it was a happy accident, but I just think I was so in the mindset of what I was doing that it all just kind of pieced together and linked somehow.I was also searching for a way to give power to the audience. I’m still in charge, but I also give power to the audience. I didn’t like the idea of just me being on stage, I write, and I produce everything, but without people, I’m nothing. Without an audience, we, as performers, have nothing. So I wanted to make it a collaborative thing.

Is what we’ve seen the original version you came up with?

I then went through a couple of versions of this. For instance, at first, I wanted to do a piece in the dark where I was talking, and it was about something like: “We’re all in this together; it doesn’t matter if you’re Black, white, female, male, trans.” In the dark, your physical appearance doesn’t matter because you can’t see the person. I might dislike you in real life, but – in this space – I don’t know where you are, and I have to interact with you to get the tasks done. But it came across as preachy, and then I went back to the drawing board.

Why did you choose to name the polar bear Cuddles?

I decided on Cuddles because it would be a counter puzzle. Polar bears are vicious, all bears are vicious, and then being like, “Oh well, I guess if you’re in a zoo, you want to make the animals seem friendly.” So I just thought it’d be funny.

The polar bear is also a highly symbolic image in other contexts. For some, the performance seemed more related to the hierarchy between animals and humans, while for others, it was between Blacks and whites. Was this intentional?

It wasn’t my intention. One of my main intentions was about race, identity and community. These were the three things that I was focusing on. But I suppose that something that comes with opening it up for you all to have your own thoughts or take charge is that you’re free to think about what you want in your performance. Is it about climate change? Is it about animal abuse and zoos? Is it about race? Is it just about stereotypes? When you guys get, hold of it is about whatever you think it is about.

You give the audience an active and participative role, not only in thinking but also in acting, which can entail some risks. Have you ever felt in danger?

Surprisingly no, I’ve personally never been in danger. At any point, though, I know that I could stand up and be like, “Nah, it’s done.” Like, too much violence, leave. If I fell and hurt myself, fine, that’s on me. But if one of you falls and you hurt yourselves, I suppose I would try to stay in character to care for them.

The Privileged forces you to deal with the stereotypes you put on yourself and on others. You suggest a meeting for the audience only following the performance to elaborate thoughts together. Have you ever thought about participating in the discussion?

Yes, I thought about it. But I don’t like it because it becomes more about me than the piece and the subject. In one of the older versions – when it was part of a festival – there was something like a question-and-answer moment, and I had a discussion with some people. I don’t know what kinds of questions I’d expect… I guess thought-provoking questions, but I’ve got questions like: “Ohh, so why did you call it the privilege?”. It doesn’t fucking matter why I called it what I called it. And you then, as an audience member, you’re searching for the right answers, expecting me to have them. I have no answers. If I’m in the room, even if I’m like, yeah, talk amongst yourselves, there’s no right, or there’s no wrong answers. It always will come back to me as in, tell me, tell me what your thoughts are. I can, but what are your thoughts? And if I remove myself from that room, you have no answers apart from what you make yourself.

What is the line between acting and real life?

It is acting but it’s also not. I am really going through this stuff. Like being treated friendly to begin with and then not because of outside being and everybody follows because it’s like society you have to do this. So you know it is real and it’s not.

What happens after everyone is out of the room? What changes in you? How do you feel after the performance??

Nothing really changes. I can talk; I’m just more vocal. Like I can speak, it’s not just growling… I suppose I process afterwards, which makes it difficult because also you, the audience, are processing. I guess some people will still talk to me like they’re searching for answers or something, or they ask me how the performance went. I don’t know how it’s gone… I don’t know how I feel… Rather than processing, I think it’s more coming back to myself slowly. And digesting.

What has changed in these nine years of performing The Privileged?

Nothing really changed, just the way I interact with people. My brain and how I go about doing things have changed. I’ve just become more comfortable in what I’m doing. If I am tired, when I’m tired, I will stop. If I still have the energy to keep going, then I will. If I feel like I’m going to be sick. It hasn’t happened, but then I will just be sick. I care a lot less about the aesthetics or making it perfect, or it’s just I will do what needs to be done in that moment.

What did you learn about yourself, others and society?

I am very stubborn; I already knew that. If I’m honest with you, I don’t know if I have learned anything. I know that I just want to perform. That’s a couple of other things that I’ve learned, actually… People will always try to seek answers from you, and you don’t have to give them to people. If someone came up to me crying, kind of wanting reassurance. I don’t have to do that. I’ve given you an hour, two hours of my time, my blood sometimes, sweat. I don’t have to be the person to make sure that you are okay. That’s not. You’re not in my care anymore. That’s all on you. Do what you need to do to figure out how to process it, because I also have stuff to process; I think that’s the main thing.

In how many countries do you do in this show?

I’ve been to the States a couple of times. Italy, three times now. I’ve been to the Netherlands and England, of course. I think that’s it, 4.

Did you find a difference based on where you were? Or a pattern of some sort?

Yes, I think… Although there are different cultures, people are all more or less the same. They want guidance, they want reassurance and they want to know they’re doing the right thing at this moment in time. But if somebody hit me, I personally wouldn’t think that they’re an awful person because I’ve asked them to do it or I’ve given you the “permission”. But I don’t think that everyone is aware of it; they seem to surprise themselves with the actions that they do in the heat of the moment. That being said, I think that the one that stands out the most, difference-wise, was the States because it’s very racially charged there. They were trying to show that they one-up each other in terms of care. They were trying to one-up each other and be like: “oh I care more so I will stay”. And then someone else would be like: “No, no, I care more so I will stay”. While if they had just left, I could have just been alone and begun healing, being me coming back to normal. I think that they’re doing it because of everything that’s happened in that piece. And they might not have even done the bad thing, but it’s a performance. I didn’t die, I didn’t lose any of my limbs.

Marta Begna, Biancamaria Gotti, Valeria Tacchi, Daiane Torres, Marie Noelle Saffo, Silvia Baldini

La RE.M Come together Up To You 2023

Dopo aver visto lo spettacolo: